Introduction to 1966

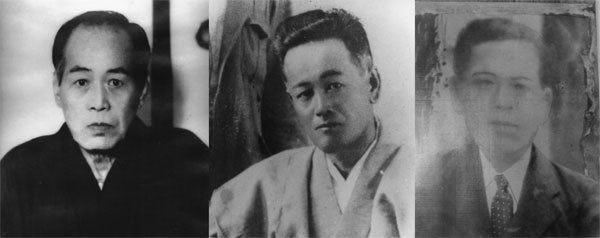

Takeshi Onaga

・Born in 1943. He became a student of Sensei Uehara Seikichi at the same time he entered high school (1959). He had done some Goju-ryu before he started. The reason I started studying with him was because a friend of mine, Shunichi Yogi, who went on to technical high school, had enrolled in the school first, and through that connection, I decided to enroll as well. He became a judo champion in middle school and moved to Brazil after graduating from high school.

・From that time on, Uehara sensei called himself the Motobu style. Uehara Sensei was a disciple of Motobu Choyu Sensei. It is said that Uehara Sensei went to Wakayama to teach Choyu Sensei’s eldest son and other people his techniques. Choyu Sensei lived in Tsujimachi, and Uehara Sensei went there to sell soy sauce. That’s how he got to know Choyu Sensei and became a student. His disciples were practicing kata, but Uehara sensei did not participate in the kata practice, and at first he was forced to only practice basic thrusting and kicking while standing on his tiptoes.

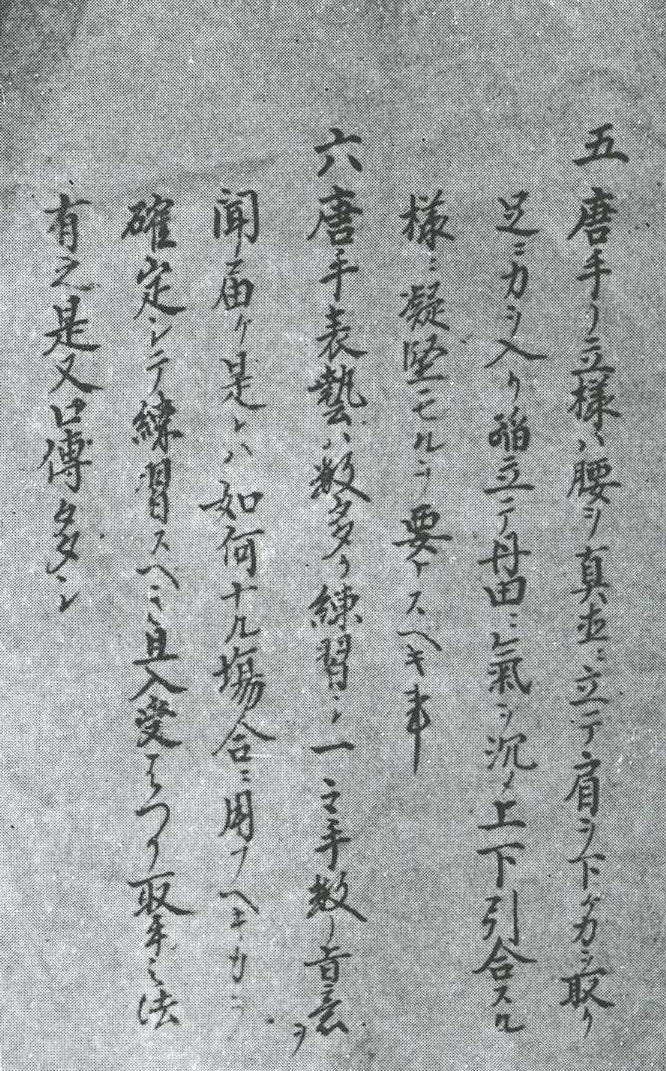

・He said that he received a Ryukyu scroll from Choyu sensei. This Ryuka was first created for Toraju (Motobu Tomoshige), and he also gave it to Mr. Uehara when he left for the Philippines. At that time, we were also made to recite these Ryukyu poems, so we can still remember some of them.

・Mr. Uehara was running a bar for the US military. Only those who passed a strict sanitary inspection were allowed to bar with U.S. military personnel .

・The rehearsal location was near Futenma Air Base, which is now lined with houses, but at the time it was just a grave or a field, so we could practice there. We also practiced on the wooden floor of a bar run by Mr. Uehara.

・I think there were about 3 disciples including me. Uehara Sensei did not publicly announce that he was teaching karate. All of the beginners were introduced by acquaintances.

・The first practice consisted mainly of punches and kicks. He put on boxing gloves and practiced by punching Uehara Sensei directly in the stomach and having his punches knocked away. At the time, there was a person who was about 20 years older than me, and I practiced with him as well. The person was roughly poked in the face, but Uehara-sensei’s skill is high, so that didn’t happen.

・The thrust could be from either the left or the right, but it was always done with the front hand. It is a thrust similar to a jab in boxing. At that time, there was no other school in Okinawa that used the technique of thrusting with the front hand (what we call today’s kochizuki), so I think it was extremely rare. Normally, the standard style in this day and age is to have the front hand be the receiving hand, and the tsuke to be thrust from the pulling hand. He was also taught to kick with his front legs. I kicked him in the front with the ball of my foot.

・I was taught how to stand on my tiptoes and not bend my knees. This is still true in Gotente, but it was also taught back then.

・After practicing mainly thrusting and kicking, we moved on to practicing thrusting and throwing. Uehara-sensei will throw the ball to whoever hits it. Mr. Uehara’s throwing style was not like in Aikido, where he went around and around, but instead threw the ball directly at the person he hit, or he threw the ball with his feet. Another method of throwing was to wrap the right hand around the opponent’s neck.

・I think I was taught three or four kata, but I didn’t have any interest in kata and mostly focused on kumite, so I don’t remember much about them now. I learned the three techniques of open hands and fists. Umeichi Matsuda and Yogi, who immigrated to Brazil, mainly practiced for three games. The three battles taught by Uehara Sensei were not about moving forward and how many steps you have to take before turning around. In practice there is no such reversal, just going all the way forward. The third match was played by those who were physically able. He put a lot of effort into it. I was careful with my fists.

・In 1961, the first Kobudo Tournament was held at the Naha Theater. Most of the contestants were people who had their own dojos, but were small in size, had few disciples, and were not well known. Seitoku Higa Sensei hosted this tournament. I also went to see the tournament, but the young players did not participate in this tournament. Mr. Uehara demonstrated Jichin.

・I had heard from the beginning that there were handles, so I said, “Sensei, please tell me about that too,” but he didn’t tell me right away. After he had practiced throwing, he finally learned how to handle. He is in his fourth year at the school. He said that Toride includes not only joint techniques but also throwing techniques. I went to Ryukyu University and was also a member of the karate club. In college, I was passionate about kumite, so I was involved in both Hombu-ryu and Kumite.

・At that time, Uehara Sensei was in contact with various teachers, and they were also doing kumite research together. He also taught Toride to such people. However, there were some who were critical of it behind the scenes, such as “It’s different from karate” and “Isn’t that kind of technique (toride) even in karate?” Even back then, Mr. Uehara had been using the word “tweity,” but he said he had never heard of such a word or that he thought it was strange. To tell you the truth, back then I was too embarrassed to say that I was learning Toride, so I just said that I was learning Karate. In any case, many people thought that the martial art called Toride did not exist in Okinawa.

・When asked if you were familiar with the notation “Toride” that appears in Itosu Juken (1908)>

No, I don’t know.

・Recently, other schools are also using the word Toride or teaching Toride.>

At that time, I never heard anyone other than Uehara-sensei use the word Toride. It is hard to believe that Toride has been passed down to other schools. I think those people don’t know that their master studied under Mr. Uehara. There are many people who studied under Uehara Sensei and then quit right away.

・Among the karatekas who interacted with Uehara Sensei, Nakama Asomasu Sensei (who also studied under Motobu Choki Sensei) was good at Promise Kumite. He was reasonable. He just poked me with the hand he received. Two beats are fast. He’s not pulling back, he’s just thrusting.

It’s better to use continuous techniques instead of doing each one neatly. Nakama-sensei’s naihanchi stance was scary. I got the impression that it was powerful and difficult to approach.

・Okinawa Kenpo teacher Shigeru Nakamura is a pioneer of practical karate. The first person in Okinawa to compete in armored karate. At that time in Okinawa, people said, “If you compete in karate, one person dies,” so they only practiced kata. Isshin-ryu’s sensei Tatsuo Shimabukuro also practiced karate against the U.S. military after the war.

・I accompanied Mr. Uehara to the Hakkoryu training course, but it only took about 10 minutes a day. I was always with Uehara Sensei during the training sessions, but Uehara Sensei hasn’t adopted any techniques from Hakkoryu since then. After the seminar, a man named Yasuda, who was helping with Hakkoryu, stayed in Okinawa for about a month and practiced with Uehara Sensei.

・When asked by Yasuda Sensei that Uehara-sensei didn’t learn any techniques at the seminar, and that he already had a sealing technique, I heard that.>

Toward the end, I took the role of holding the handle while practicing, but even when I grabbed Uehara-sensei’s hand, it often slipped through. How could such a thing happen? He probably knew the techniques to pull out the handles and seal them. I don’t know if it’s natural or the result of training. I also learned a little bit from Mr. Yasuda, and he was quite skilled. If the person didn’t use the technique, I think Uehara-sensei actually knew the binding technique.

・Weapon techniques included stick to stick, stick to sickle, stick to nouchik, etc., but I didn’t practice them too hard because I wasn’t interested in weapon techniques.

・I haven’t learned Hamachidori. It is said that Shuri Matsumura was also a good dancer.

・When asked, Mr. Higa Seitoku advocates the theory that the toride was passed down from Matsumura Soukan.>

I’ve heard Higa Sensei say this, but I’ve never heard it from Uehara Sensei.

・From around 1965 or 1965, people started practicing wearing kendo masks and torsos. Also, around this time, several American military personnel began coming to practice.

・His other disciples at the time included Tsunami Takaaki Sensei and Higa Seitoku Sensei from Nago. Both were very enthusiastic. Tsunami Sensei was just over 50 years old at the time, and was quite an expert, and Uehara Sensei had high hopes for him, but he died in a traffic accident on his way home from practice. Motoyoshi Omura was also there, but he only came to practice once in a while. Mr. Omura is Tsunami Sensei’s brother-in-law and a disciple of Nakamura Sensei. As for Hiroshi Uehara, we didn’t meet because we were practicing during the day (because we were practicing at different times).

・At that time, there were no ranks or diplomas, only white belts and black belts. When I was 26 years old, I received the rank of 5th Dan Renshi from the All Okinawa Karate Kobudo Federation (chairman: Kiyonori Higa). That is the first and last time.

・After that, I got a job at Ryukyu University and started instructing the karate club, and as I became busy with university karate, I left the Hombu style.

・About Uke techniques

There were no uke techniques such as uchi-uke and soto-uke that are often seen in karate. There is no dandanbarai to receive a kick. Uehara-sensei dodges and pokes at the same time. It feels like dodging with a thrust. It’s a kind of counter. It’s difficult without a lot of practice. If you don’t just practice mechanically, it’s impossible to become as good as Mr. Uehara.

・His physical handling was good. Standing on tiptoe is to dodge the body quickly. In the story, he said that he could lift his heel high enough to pull a piece of paper through. If you lift your heels too high, your knees will turn into sticks. Even back then, Mr. Uehara did not bend his knees, but even when he was straight, there was still some room in his knees. He just didn’t bend it enough to be noticeable. At that time, there was no school in Okinawa that did not bend the knee. Front bends and cat feet were the mainstay of kumite in Okinawa.

・Mr. Uehara was strong. His logic and ability matched each other. He once did a demonstration in the Ryukyu University gymnasium where he gave Kanzo Nakamura a large kitchen knife – or rather, something more like a machete – and let him attack it freely, and he was able to handle it all. Even if it’s a promise, it’s a real knife, so if there’s a mistake, it’s a big deal. However, Mr. Uehara was able to do it. There was a lot of bad talk from the outside, asking if he could do something like that, wondering if it was an arrangement, and wondering what would happen if he tried to feint, but Uehara-sensei was able to do it. Uehara sensei’s technique of dodging the body was something that no one else could imitate. He said, “Dodge the fist as if it were a knife. You only get one shot.”