Translated by Lucas Barboza

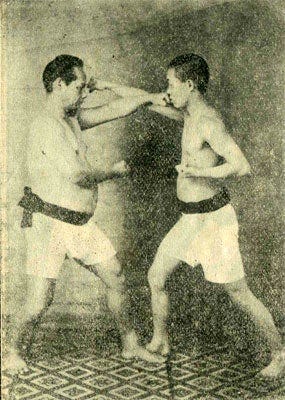

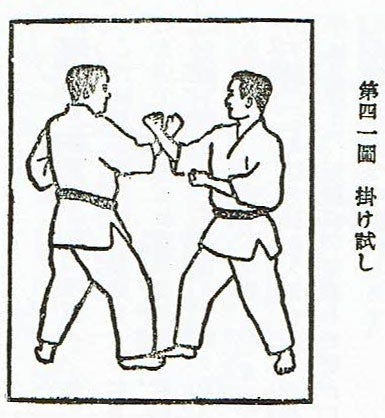

Kakede 掛け手 (or Kakidī in Okinawan dialect) is an ancient form of Jiyū Kumite or free combat, commonly interpreted as “hooked hands” or “locked hands”. Sometimes this is also referred to as Kake-kumite. This form of combat is called this way because it begins with the forearms of both opponents being hooked together [see the photo below].

Chōki Motobu enjoyed the practice of Kakede. He used to say that “it leads to acquiring an expert eye.” Since Kakede makes free use of attack and defense, one can react instantly to an opponent’s attack and defend oneself, or one can attack instantly without missing an opening provided by the opponent. This is because Kakede cultivates these types of reflexes or quick reactions. These skills or insights are difficult to acquire just by striking the Makiwara or practicing Yakusoku Kumite which only performs predetermined attack and defense actions.

Furthermore, combat in the Kakede position was also called “Kakedameshi” (or Kakidamishi in the Okinawan dialect). Kakedameshi essentially means “test/experiment (fighting) carried out in Kakede”, however nowadays this meaning seems to have been generally forgotten.

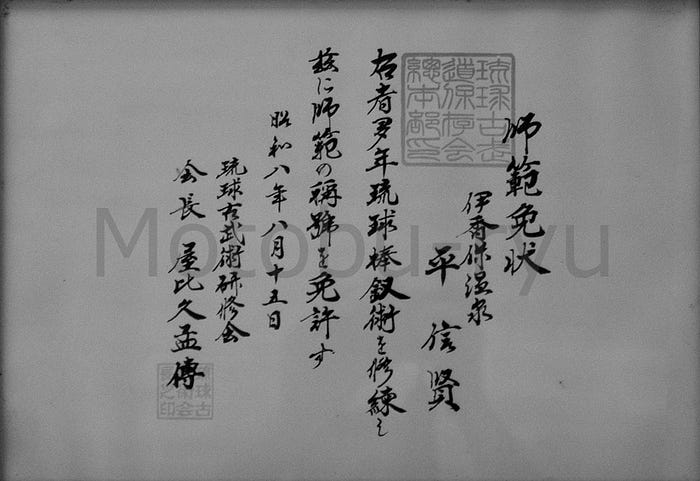

By the way, as far as I know, Kakede appears to only remain in existence in Motobu-ryū currently. Therefore, some people may wonder whether practice methods like Kakede actually existed in Okinawa. However, Kakede had been presented by Kenwa Mabuni and Genwa Nakasone in the “Introduction to Karate-Dō: Offense and Defense” (1938) before the war.

Introduction to Karate–Offense and Defense Kempo

Amazon.com: Introduction to Karate – Offensive and Defensive Boxing: 9784898051184: Books

a.co

We can observe the following passage in this work.

In Kakidī (See Fig. 41), both sides must cross their forearms on the outer side (below the wrist and thumb side). It’s the same thing you do when you cross the tips of your swords in Kendō. You never know how the opponent will transition. In Okinawa, they usually call this Kake-dameshi and often try to “hook” (hikkake) each other’s good techniques (i.e., crossing fists in the Kakidī stance). It is said that you can measure and determine an opponent’s skill just by hooking your forearm with theirs. If you then find that someone else’s hook matches yours in skill, you can exclaim: “Let’s begin!” or say “Are you ready?” to compete their techniques. (page 117)

This book is “co-authored” by Kenwa Mabuni and Genwa Nakasone, but in reality the author is Genwa Nakasone, with Kenwa Mabuni being the general editor (supervisor) of the book. In his book “Karate Kenkyū” (1934), Genwa Nakasone published an article in which he interviewed Chōki Motobu and which was published before the 1938 book with Kenwa Mabuni. In this way, Nakasone must have heard the above report from Chōki Motobu.

Karate research (Okinawa studies research materials (5))

Amazon.com: Empty-Hand Research (Okinawa Studies Research Materials (5)): 9784947667922: Books

a.co

Genwa Nakasone, “Karate Kenkyū” (1934)

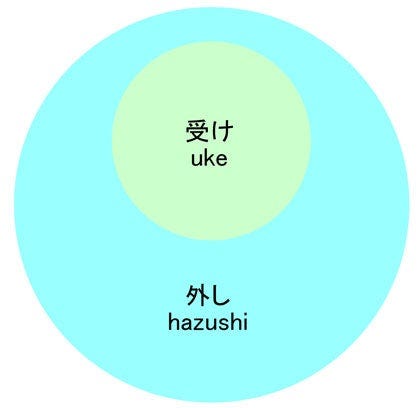

In any case, we can see that “Kakidī” is not a creation or fabrication of recent years. By the way, I am sometimes asked if Gōjū-ryū’s “Kakie” and Motobu-ryū’s “Kakidī” are similar things. I think that when analyzing the practice of Kakie, I can see that it is a “strengthening method” (tanren-hō) in which the arms are pushed and pulled against each other. Motobu-ryū’s Kakidī, in turn, is a completely free Kumite. For this reason, I believe that both exercises are completely different things.

In fact, there is a similar practice method in Chinese martial arts, but when I asked a person who had been studying Chinese martial arts, she distinguished a practice method like Kakie as being “Tuīshǒu” (pressing hands/compressed hands). and a practice method such as Kakidī [which includes striking] as being “Sànshǒu” (spread hands/free hands). Even though Kakie and Kakidī start from the same position, they are different exercises.

Therefore, it appears that Kakie and Kakidī were originally different methods of practice, even though they both originated in China. As far as I know, the Kakie was brought from China by Kanryō Higaon’na or possibly Chōjun Miyagi during the Taishō era (1912–1926), furthermore, I believe the Kakie was brought to Okinawa at a different time than the Kakidī.

By the way, there is no mention of Kakie in the book “Introduction to Karate-Dō: Offense and Defense” mentioned above. Furthermore, to this day I have not read any other book or article whatsoever that mentions Kakie in the pre-war era. Therefore, it may not be so easy to investigate Kakie’s exact transmission lineage these days.

The original Japanese article was published on February 1, 2019 in Ameblo; the Portuguese translation was published on March 5, 2021.

Thank you for reading my story. If you want, follow me

Written by:

Thank you for reading my story. If you would like, please follow me.

Shihan, Motobu Kenpō 7th dan, Motobu Udundī 7th dan. Discusses the history of karate and martial arts, and introduces Japanese culture and history.